Scalable Recommender Systems Architectures for E-Commerce

In this post I describe how I built a personalised recommendation and item-similarity pipeline capable of inference at scale. To do this I used the Nvidia Merlin framework optimised for GPU and Triton Inference Server for inference.

Dataset

I employed a dataset from the H&M Personalized Fashion Recommendations Kaggle competition, it is one of the most extensive and realistic datasets available for e-commerce use cases, comprising 35 GB of data across four different databases:

- Customers: Basic information such as name, age, gender, location, and occupation for 1.4 million H&M customers.

- Articles: Product information including title, category, and color for over 500,000 H&M products.

- Images: Photos of each product in the articles dataset.

- Transactions: Detailed records of past transactions per customer, including products bought and prices paid.

Personalised Recommendation Pipeline

Muti-stages pipeline architecture

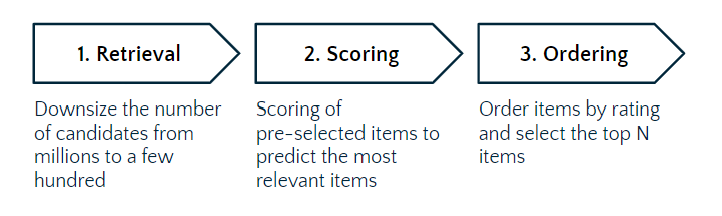

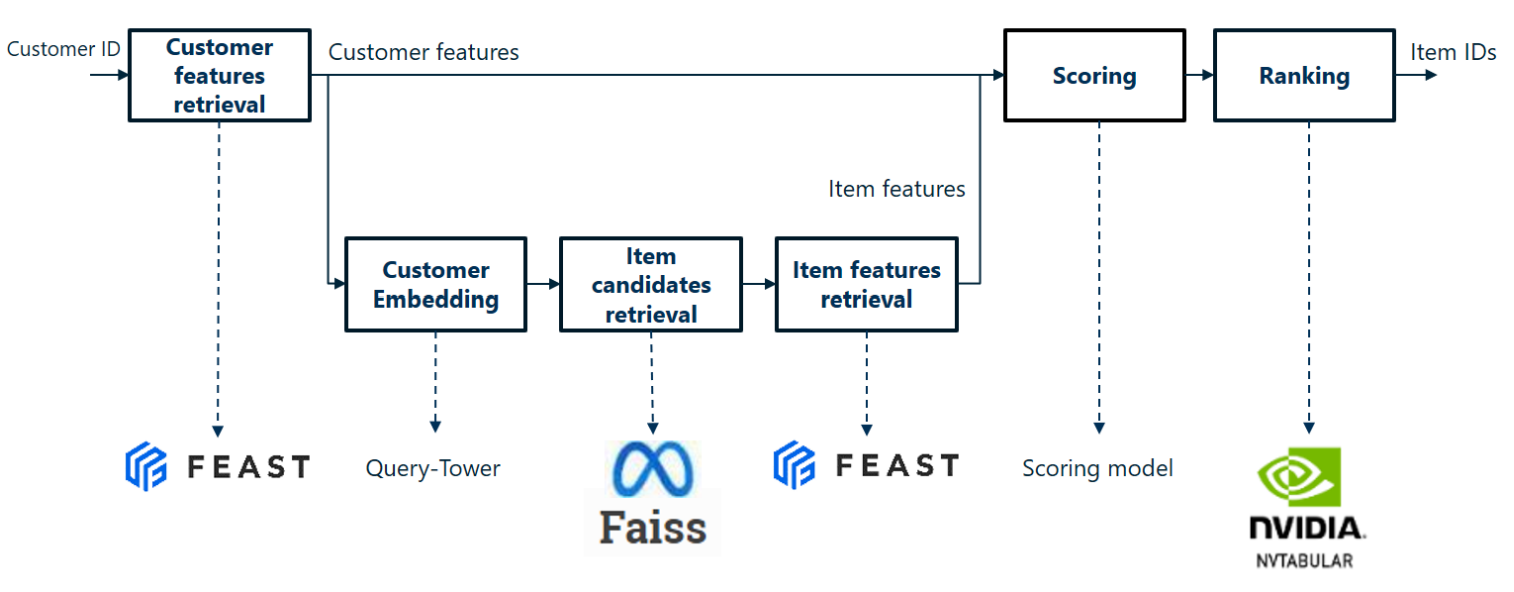

A personalised recommendation pipeline consists of returning a list of items relevant to a given user. However, there can be a huge number of potential products. In order to speed up inference time, in-line recommendation pipelines are often made up of several stages, including a rapid retrieval stage to reduce the number of candidates, followed by a more precise scoring stage to determine the best products to recommend. The figure below shows the common architecture of a multi-stage recommendation pipeline.

Retrieval

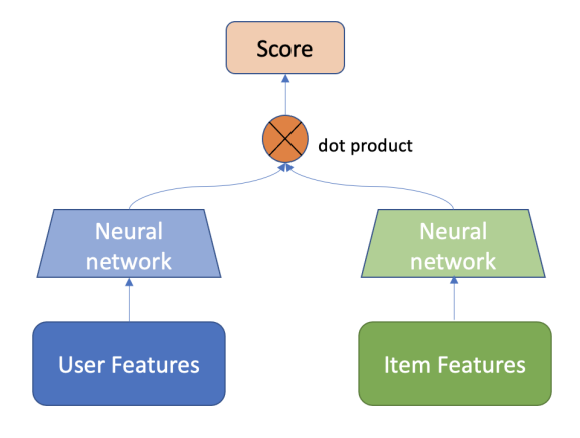

For the retrieval part, I choose the widely used Two-Tower model. The aim is to get a sub-selection of items as fast as possible. The Two-Tower model match users with items by learning separate embeddings for users and items in two separate neural networks.

The Two-Tower trick for fast retrieval

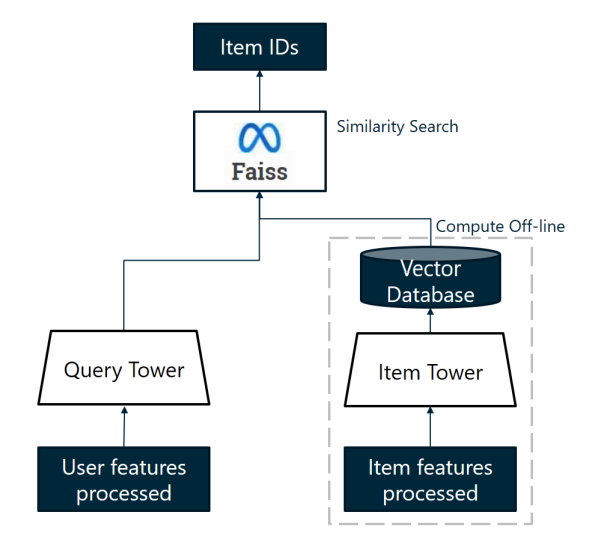

The advantage of the Two-Tower model is that item embeddings resulting from the Item-Tower can be computed off-line. There is no need to to recalculate embeddings for all items for each inference. The only thing left to do in-line is to compute the user’s embedding by passing his features into the Query-Tower (or User-Tower) and to compute the dot product with all the pre-compute item embeddings. However, the process can still be improved. By registering the items’ embeddings in a more clever way, we can use approximate vector search algorithms that directly return N vectors among those most similar to the user’s embedding vector in a very short amount of time. This can be done by FAISS.

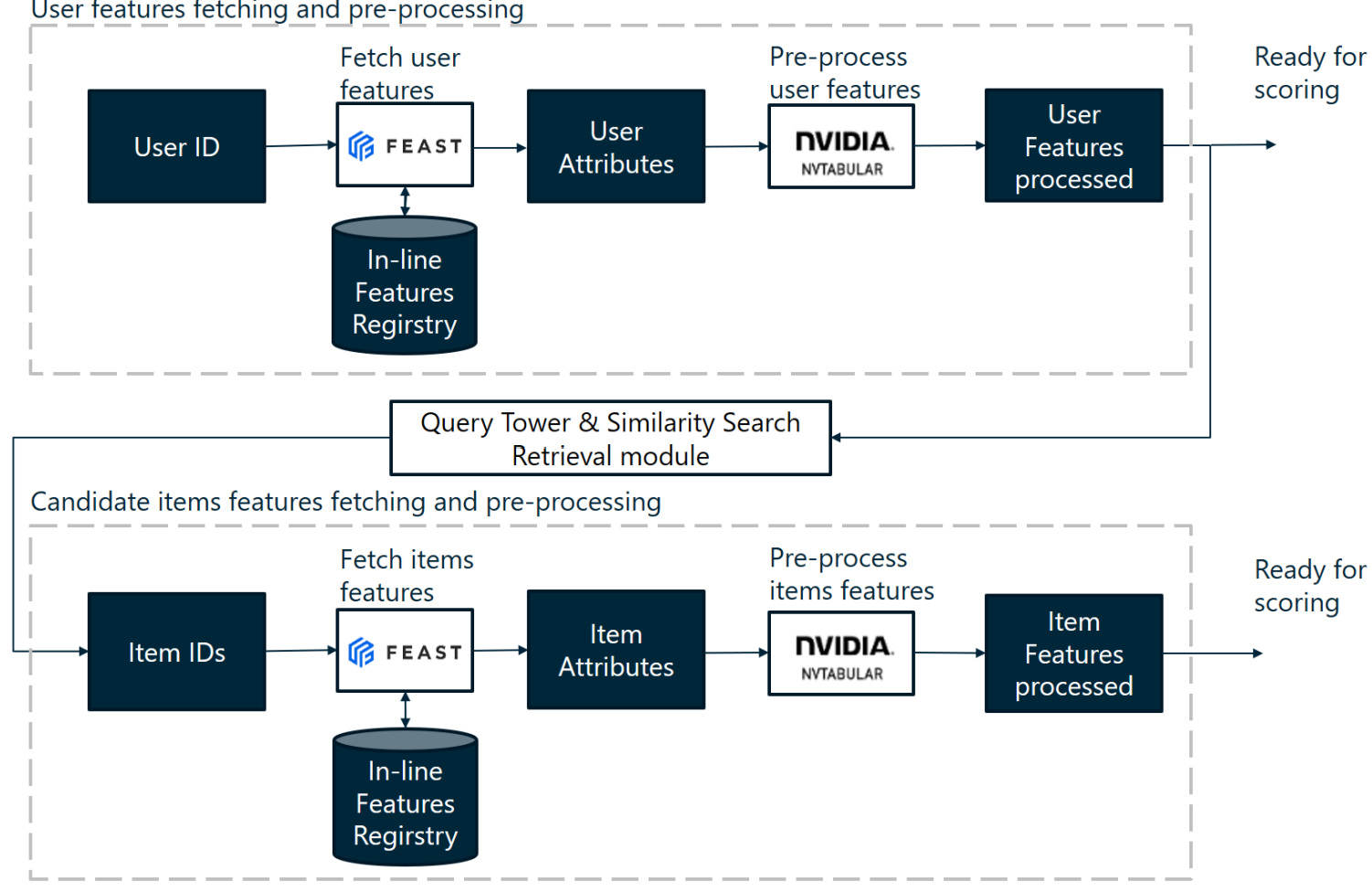

Features fetching and pre-processing

The aim of a recommendation system is to give it a user id and have it return a list of item ids. So, given a requested user id, we need to retrieve the user features from a database to give it to the Two-Tower model. I used Feast feature store for this purpose, I saved the raw data (customer and product features) in the Feast feature registry and during inference, Feast takes care of retrieving the features associated with the user id.

As this data is raw, it needs to be processed so that it can be given as input to the Query-Tower of the Two-Tower model. Most customer and product features are categorical and need to be associated with integers. In short, this pre-processing stage is used to transform the raw attributes of the database into processed numerical data similar to the data used to train the models. To do this, I used Nvtabular, which allows me to save workflows of pre-processing operations during development and deploy them in production. This data retrieval and processing pipeline is also applied to the candidate items from the similarity search.

Ultimately, the aim of the retrieval pipeline is to have processed the user features and those of the candidate items to give them to the scoring algorithm.

Scoring and Ordering

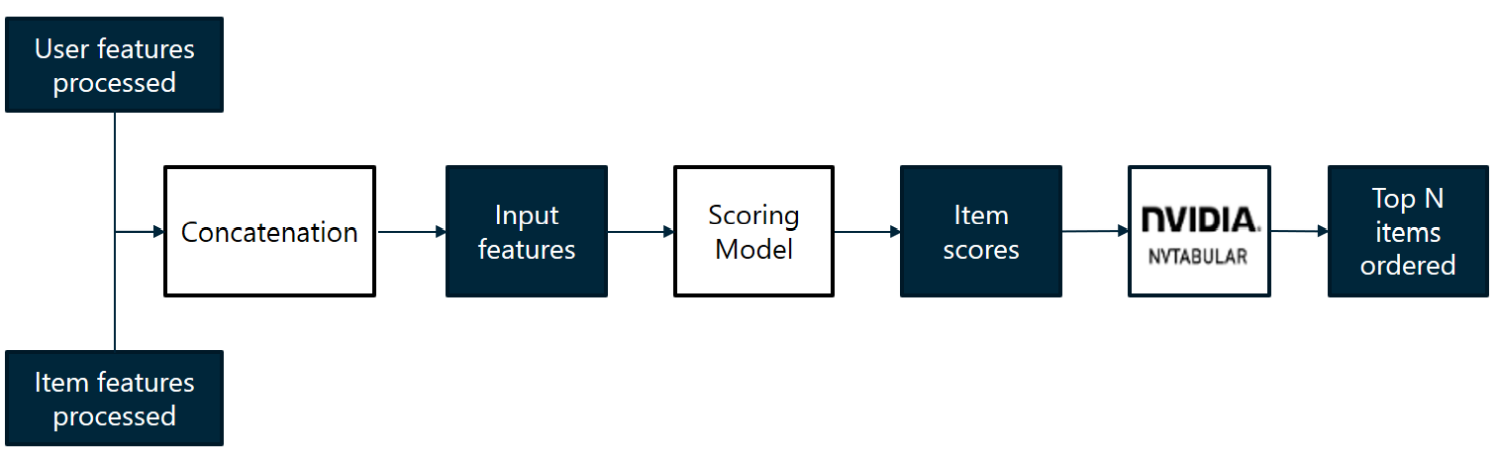

Once the features have been processed and retrieved from the user and all the candidate items, all we have to do is concatenate them and give them as input to our scoring model. This finer-grained scoring model is often a supervised model such as DRLM or Wide&Deep. This model gives scores for each item, so all we have to do is choose the N-best items, order them and return their ids, and that’s it, the personalised recommendation pipeline is complete.

Pipeline overview

By combining the retrieval and scoring pipelines, we can get an overall picture of the personalised recommendation pipeline. The following figure is an overview of the pipeline and its main components.

Inference example

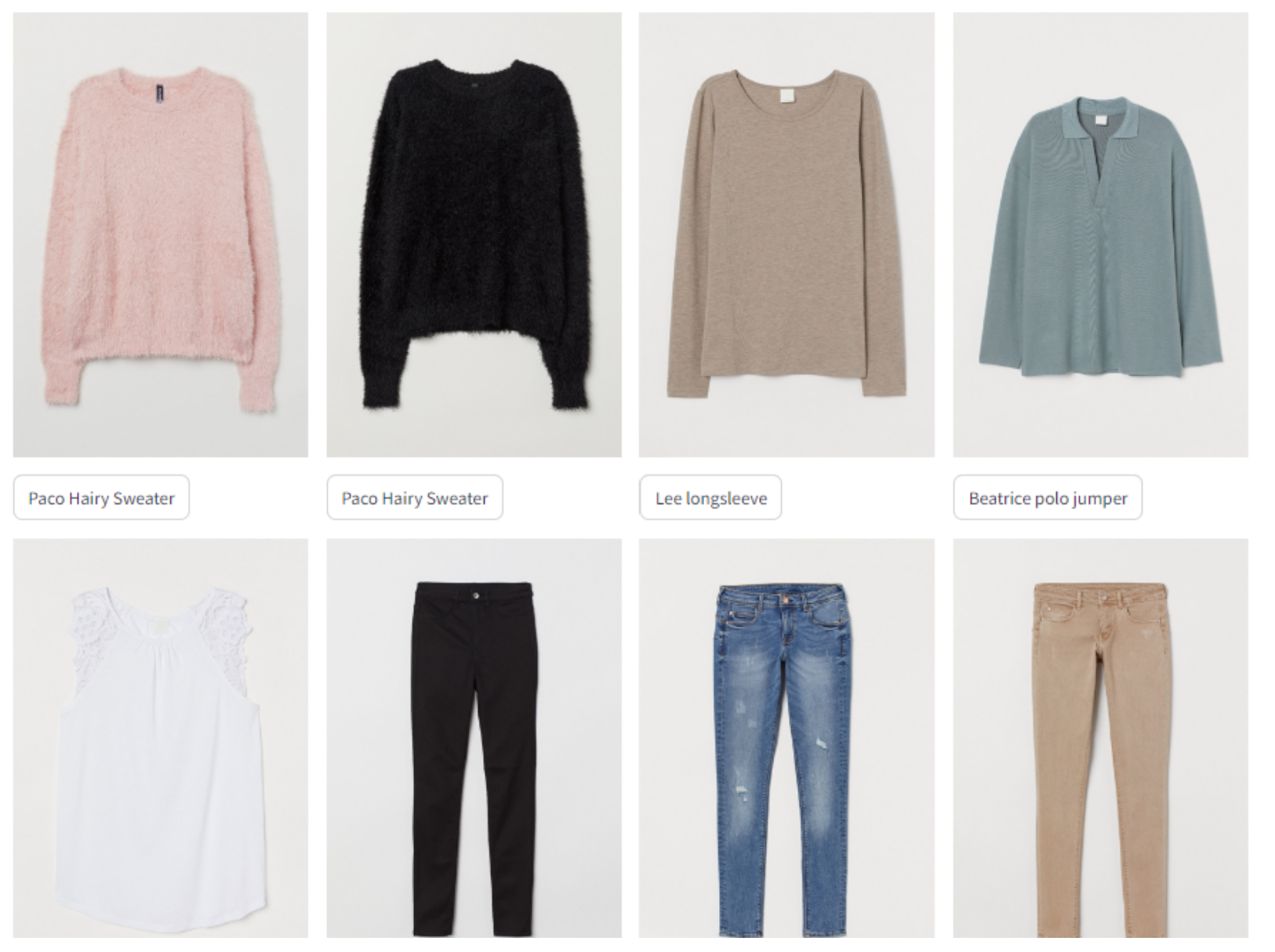

Let have a look on the recommendation provided to a random H&M customer on a fake website demonstrator I built:

Item-similarity Recommendation Pipeline

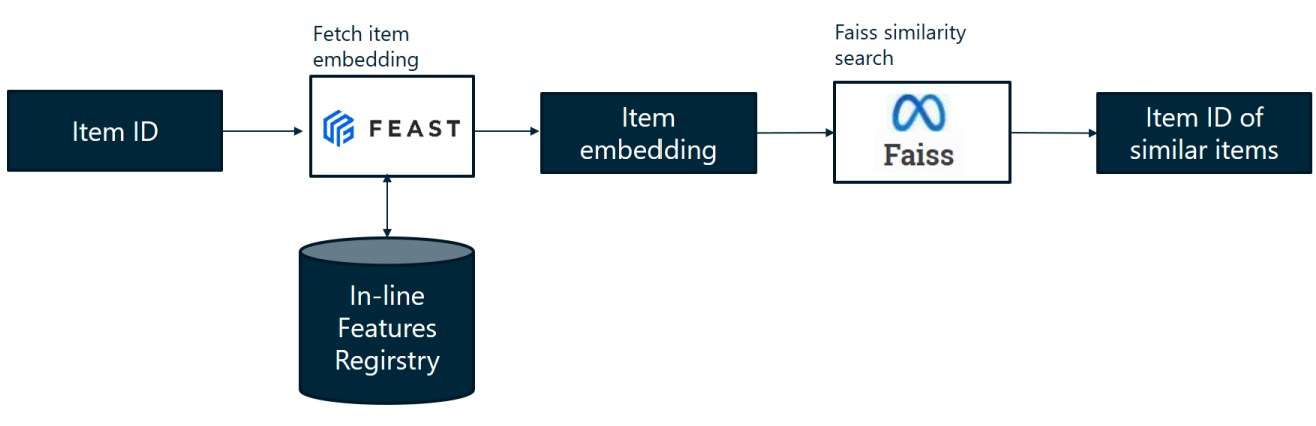

The aim of an item similarity pipeline is to suggest products that are similar to the product consulted by the user. This option is very popular on e-commerce websites, making it easier for users to browse products they like. This pipeline is much simpler than the previous one.

Architecture

The aim is to return a list of items that are similar to a given one, which is an content-based recommender system. To do this, we simply retrieve the item’s embedding and compare it with the embeddings of other items, with Faiss for example, and return a list of similar items.

The overall structure of the pipeline is detailed in this image.

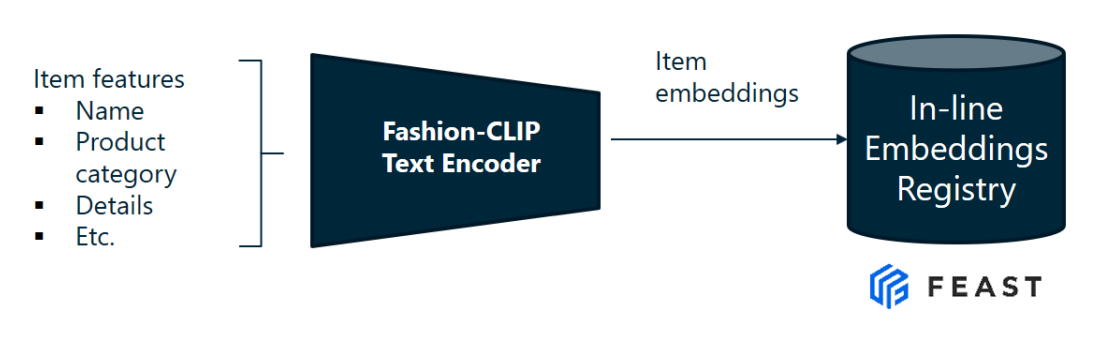

FashionCLIP Embedding

To achieve a good level of similarity between the articles recommended, it is important to have precise enough embeddings. I chose to use Fashion CLIP to create the fine-grained embeddings. FashionCLIP is a domain-specific adaptation of the CLIP model, fine-tuned to produce general product representations for fashion-related items.

The H&M dataset contains all the product features as well as photos of the products on a white background which is perfect for Fasion-CLIP. However, I decided not to use the visual features to generate the embeddings and only concatenate the product characteristics and embed them using the text encoder. The H&M product descriptions are sufficiently detailed and standardised to generate high quality embeddings.

Inference example

We can have a look at the demonstrator I build and browse similar products. For example, let’s look at this pink sweater:

The Item-similarity pipeline recommends the following items:

As you can see, these items look the same.

Inference times

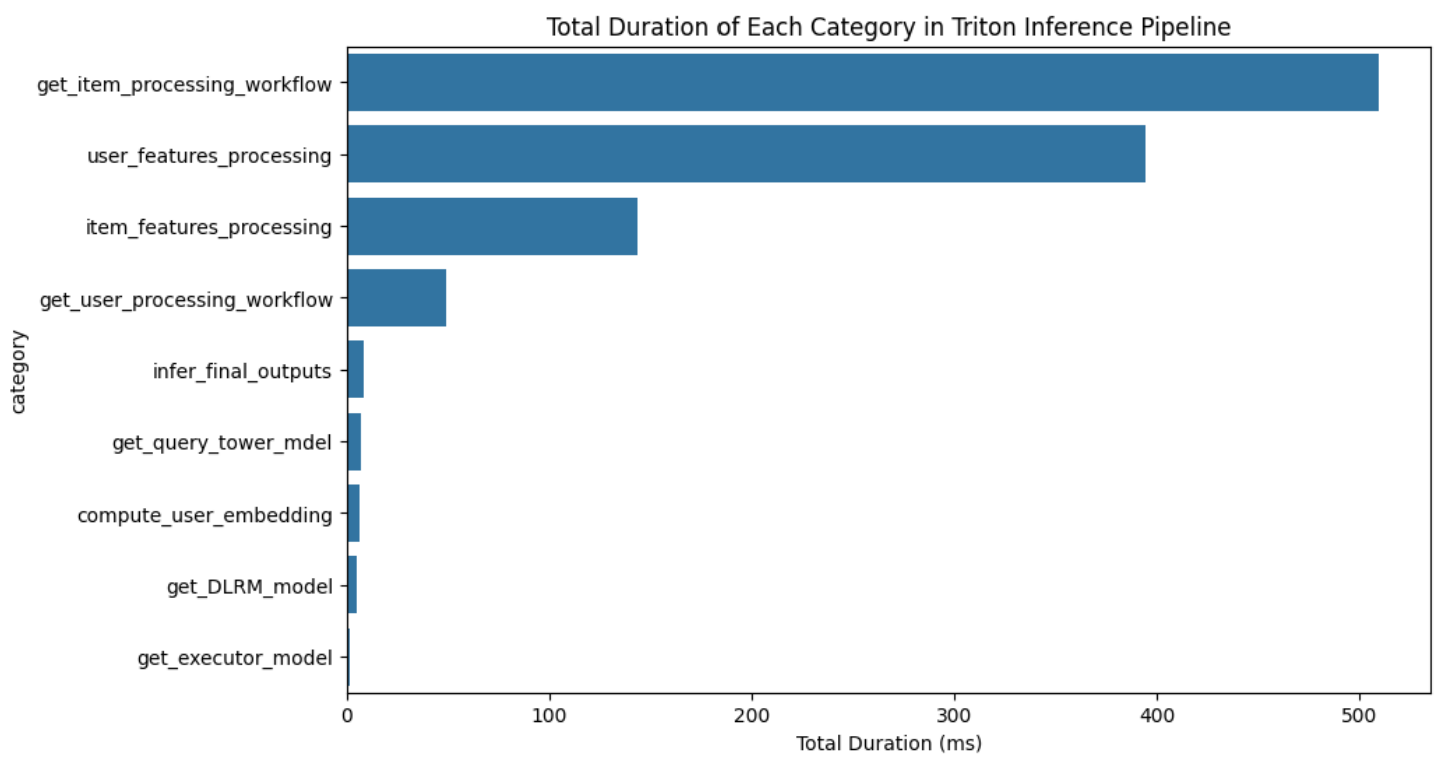

The inference time is about 1.4s for the customized recommendation pipeline and 1s on average for asynchronous inference. The inference time is about 0.3s for the item-similarity pipeline. This is still quite long for in-line inference. Using Triton logs, we can look at the detail of inference times.

As illustrated in the figure, the most time-consuming part of the pipeline is getting processing workflows and processing the raw data from the feature store. These steps alone account for approximately 1.2 seconds, or 80% of the total inference time, which is significant. On the other hand, retrieving the models (QueryTower and DLRM) is extremely fast, as they are preloaded into RAM when the server starts.

A potential optimization could be to store the preprocessed data directly in the feature store, rather than storing raw data and processing them during inference. This change could drastically reduce the total inference time, potentially saving as much as 1 second.

However, this approach raises a question: why store raw data and process it in-line during inference?

The answer depends on the use case. Real-time feature transformation allows for greater flexibility and operational scalability. For example, if new customers register or new products are introduced, their row data can be directly integrated into the feature store, and the pipeline will continue to function seamlessly. This pipeline is plug-and-play on the CRM system. Moreover, in-line processing simplifies development, as the database remains static and only grows in size.

In contrast, storing pre-processed data would necessitate running the feature transformation pipeline before every data update and loading the processed data into the feature store, complicating maintenance.

In summary, there is a trade-off between faster inference times and operational complexity. For use cases where recommendations are generated offline (e.g., weekly product recommendations), sacrificing some inference speed for a simpler, more maintainable system could be a more practical choice.